Herbal energetics comparison is the analytical study of how diverse traditional medical systems—including Western Herbalism, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda, and Rongoā Māori—classify medicinal plants based on their qualitative effects on the body. This practice focuses on universal properties such as temperature (hot/cold), moisture (damp/dry), and tone (tension/relaxation) to match remedies to a patient’s specific constitution, bridging the gap between ancient wisdom and modern holistic application at our Home.

The Core Principles: Temperature, Moisture, and Tone

To truly understand herbal medicine, one must look beyond the reductionist lens of chemical constituents and engage with the functional language of nature: energetics. While modern pharmacology asks “what chemical is in this plant?”, traditional herbalism asks “how does this plant change the environment of the body?” This is the foundation of herbal energetics.

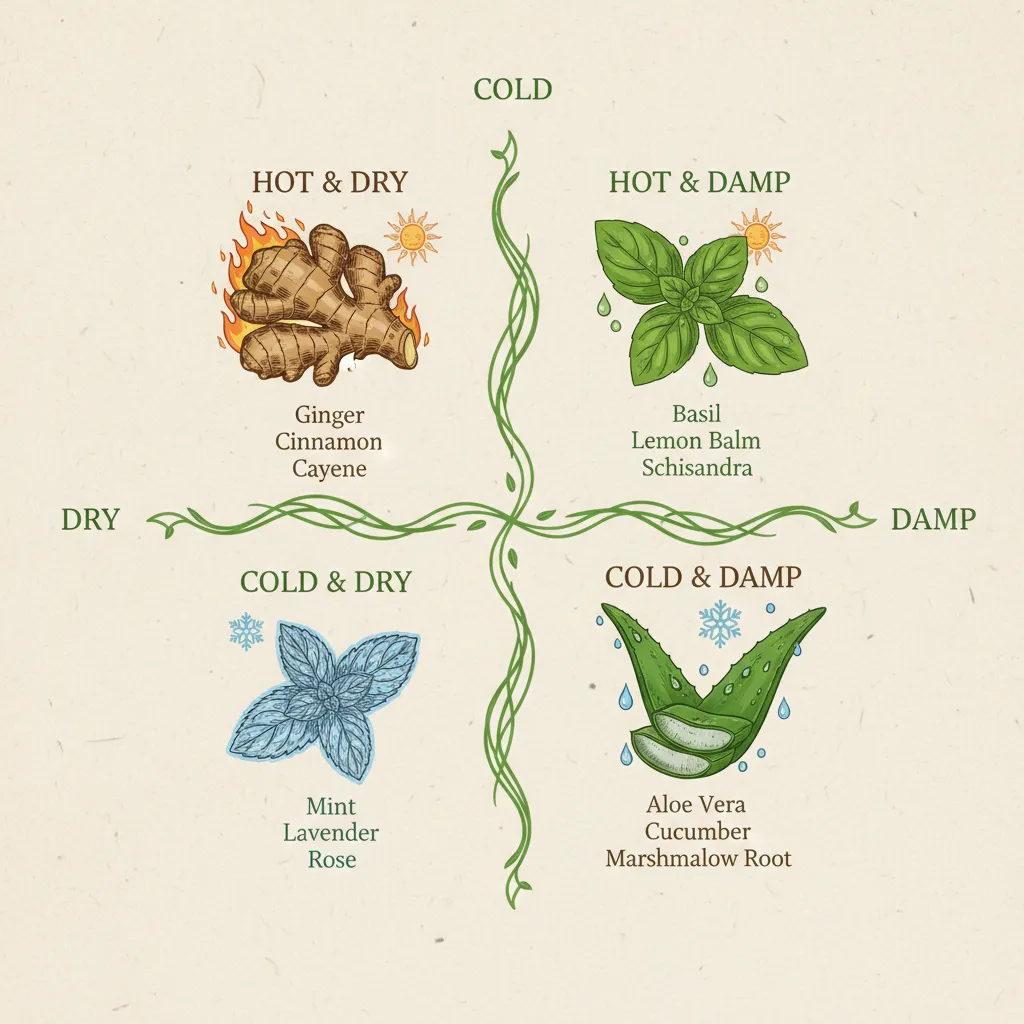

Regardless of the cultural system, most energetic frameworks operate on three primary axes. Understanding these is crucial for any herbal energetics comparison.

The Temperature Axis: Hot vs. Cold

Temperature refers to the metabolic impact a plant has on the body. Heating plants stimulate blood flow, increase metabolic rate, and push energy outward. Examples include Cayenne, Ginger, and the New Zealand native Horopito. Conversely, cooling plants reduce inflammation, slow down overactive metabolism, and sedate heat. Examples include Mint, Aloe Vera, and Kumarahou.

The Moisture Axis: Dry vs. Damp

This axis describes how a plant regulates fluids, a process also explored in the context of Hydrotherapy: Healing with Water. Drying (astringent) herbs tighten tissues and reduce secretions; these are essential for conditions involving excess fluid, such as edema or running noses. Dampening (demulcent) herbs add moisture and soothe dry, irritated tissues. Marshmallow root is a classic demulcent, while Witch Hazel is a classic astringent.

The Tone Axis: Constriction vs. Relaxation

Tone refers to the structural tension of the tissues. Relaxant herbs soothe muscle spasms and tension (think Kava or Valerian), which are foundational for the Holistic Management of Insomnia, while tonifying or astringent herbs add structure to lax, weak tissues. In the Physiomedicalist tradition, this is often described through “tissue states”—identifying whether a tissue is atrophied, stagnated, or constricted.

How Different Traditions Classify Plant Actions

While the underlying physiological observations are often similar, the nomenclature and philosophical frameworks differ significantly across cultures. A comparative study reveals that these systems are often describing the same territory with different maps.

Western Herbalism: From Galen to Physiomedicalism

Western energetic herbalism has its roots in Greek medicine, specifically the work of Galen and Hippocrates, who classified health based on the Four Humors: Blood (Hot/Moist), Phlegm (Cold/Moist), Yellow Bile (Hot/Dry), and Black Bile (Cold/Dry). In the 19th century, this evolved into Physiomedicalism, which focused on tissue states. A Western herbalist might classify a fever not just as a high temperature, but as a state of “Excitation” requiring cooling, relaxant herbs.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

TCM utilizes the framework of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water). In this system, energetics are tied to organ meridians. A plant is not just “cooling”; it might be described as “clearing heat from the Liver” or “nourishing Kidney Yin.” The sophistication of TCM lies in its ability to categorize complex patterns of disharmony. For further reading on the foundational texts of this system, the history of Traditional Chinese Medicine offers deep insights into these classifications.

Ayurveda: The Science of Life

Ayurveda, the traditional medicine of India, classifies plants based on their effect on the three Doshas: Vata (Air/Ether), Pitta (Fire/Water), and Kapha (Earth/Water). Energetics are determined largely by Rasa (taste). For example, the pungent taste increases Pitta (heat) but decreases Kapha (dampness/heaviness). The post-digestive effect, known as Vipaka, is also considered, adding a layer of complexity regarding how the herb acts after metabolism.

Energetics within the Context of Rongoā Māori

In the context of Aotearoa (New Zealand), Rongoā Māori offers a unique perspective that transcends physical energetics. While Rongoā practitioners certainly understand the physical properties of plants—knowing which leaves draw out pus (drawing/drying) or which barks soothe the stomach (demulcent/anti-inflammatory)—the classification is intrinsically linked to Mauri (life force) and Wairua (spirit).

In Rongoā, a plant is not merely a collection of “heating” or “drying” chemicals; it is a living entity with a genealogy (whakapapa). The “energetics” of a plant in this system includes its connection to the land (Papatūānuku) and its ability to restore balance to the patient’s mauri. However, for the purpose of integration, we can observe that many traditional uses align with universal energetic principles. For instance, the use of heated leaves for poultices utilizes thermal energy to move stagnation, a concept found in almost every herbal tradition.

Applying Energetic Principles to NZ Native Plants

For practitioners in New Zealand, applying the framework of herbal energetics comparison to native flora allows for a deeper clinical application of Rongoā Rakau. By observing the taste and effect of these plants, we can categorize them to help integrated herbalists select the right remedy.

Kawakawa (Macropiper excelsum)

Energetics: Warming, Stimulating, slightly Drying.

Kawakawa is often compared to Kava (its cousin) or spices like Black Pepper. Its pungent taste indicates a warming energy that moves blood and dispels cold. It is excellent for “cold” conditions such as poor circulation, sluggish digestion, or cold rheumatic pain. In TCM terms, it would be seen as moving Qi and Blood.

Mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium)

Energetics: Drying, Astringent, Cooling to Neutral.

The tannins in Mānuka give it a distinct drying and tightening quality. It is traditionally used for conditions characterized by excess relaxation or discharge, such as diarrhea or dysentery. Its antibacterial properties also suggest a “clearing” energy, removing damp-heat (infection) from the tissues.

Kumārahou (Pomaderris kumeraho)

Energetics: Cooling, Bitter, Relaxant.

Known as “Gumdigger’s Soap” due to its saponin content, Kumārahou has a bitter taste that triggers digestive secretions and cools the liver. Energetically, it clears heat from the respiratory system (useful for bronchitis) and helps the liver process toxins. It fits the profile of a “cooling alterative” in Western Herbalism.

Horopito (Pseudowintera colorata)

Energetics: Hot, Pungent, Drying.

Horopito is the “chili pepper” of the NZ bush. Its intense heat stimulates circulation immediately. It is antifungal (clearing dampness) and stimulates the digestive fire (Agni in Ayurveda). It is contraindicated in conditions of excess heat or inflammation (Pitta elevation).

The Role of Intuition vs. Scientific Classification

A critical debate in modern herbalism is the balance between intuitive energetic classification and scientific pharmacological data. Can we rely on the taste of a plant to determine its medicinal value, or must we rely solely on double-blind studies?

Organoleptics: The Science of Sensing

Organoleptics is the practice of using the senses (taste, smell, touch, sight) to evaluate a plant. This is the traditional method of determining energetics. A bitter taste almost always correlates with alkaloids or glycosides that stimulate the liver and cool the blood. A mucilaginous texture (slimy feel) indicates polysaccharides that soothe and moisten. This proves that “intuition” often has a biological basis.

Phytochemistry and Energetics

Modern science validates energetic principles through phytochemistry. We now know that the “heating” sensation of Horopito comes from polygodial, a sesquiterpene dialdehyde. We know the “astringency” of Mānuka comes from tannins binding to proteins. Research into ethnopharmacology continues to bridge the gap, showing that the “energetic” description is often a functional description of chemical actions.

The Integrated Approach

For the NZ Integrated Herbal Medicine & Rongoā Māori Hub, the goal is not to choose one over the other but to synthesize them. A practitioner should understand the pharmacological contraindications of a plant (Science) while also understanding whether that plant matches the energetic constitution of the patient (Tradition). If a patient has a “hot” constitution (high blood pressure, red face, irritability), giving them a “hot” herb like Ginseng or Horopito—even if indicated for fatigue—may exacerbate their condition. This nuance is where the study of energetics becomes indispensable.

People Also Ask

What is the difference between TCM and Western herbal energetics?

TCM energetics are deeply rooted in the theory of Yin/Yang, the Five Elements, and meridian theory, focusing on how herbs affect specific organ systems and Qi flow. Western herbal energetics, particularly the Physiomedicalist tradition, focuses more on tissue states (constriction, relaxation, atrophy) and the four humors (hot, cold, damp, dry), though both systems share the fundamental temperature and moisture axes.

How do you determine the energetics of a plant?

Energetics are primarily determined through organoleptics—tasting and sensing the plant. A pungent or spicy taste indicates heating and stimulating properties; a bitter taste suggests cooling and draining; a sour taste indicates astringency; and a sweet or mucilaginous taste suggests building and moistening properties.

Is Kawakawa considered hot or cold in herbal energetics?

Kawakawa is considered a warming and stimulating herb. Its pungent, peppery taste indicates that it increases circulation, dispels internal cold, and stimulates digestion, making it energetically similar to spices like Black Pepper or Ginger.

What are the six tissue states in Western Herbalism?

The six tissue states, popularized by Matthew Wood and the Physiomedicalists, are: Excitation (irritation/hyperactivity), Depression (low function/tissue death), Constriction (tension/spasm), Relaxation (laxity/leaking), Atrophy (dryness/lack of nutrition), and Torpor (stagnation/dampness).

How does Ayurveda classify herbal energetics?

Ayurveda classifies herbs based on Rasa (taste), Virya (potency/temperature), and Vipaka (post-digestive effect). These properties determine how an herb balances or aggravates the three Doshas: Vata (air), Pitta (fire), and Kapha (earth/water).

Can scientific pharmacology explain herbal energetics?

Yes, to a large extent. Energetic descriptions are often functional observations of chemical actions. For example, the “astringent” energetic quality is caused by tannins, the “heating” quality by pungent compounds like capsaicin or polygodial, and the “cooling/bitter” quality by alkaloids that stimulate bile production.