Curcumin bioavailability refers to the rate and extent to which curcumin—the primary bioactive compound in turmeric—is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and becomes available for physiological use. As noted on our Home page, because standard curcumin is poorly soluble in water and rapidly metabolized by the liver, improving bioavailability requires specific delivery mechanisms, such as combining it with black pepper extract (piperine), lipids (fats), or utilizing advanced liposomal and phytosome technologies.

The Paradox of Turmeric: Potent Potential, Poor Absorption

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) has been a cornerstone of Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine for thousands of years. Revered for its vibrant golden hue and distinct flavor, it is more than just a culinary staple; it is a repository of curcuminoids, the active compounds responsible for the root’s potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. However, modern pharmacology has uncovered a frustrating paradox regarding this “Golden Spice”, similar to the research surrounding Echinacea for Immune Support: Myth vs. Reality: while its therapeutic potential is immense in a petri dish (in vitro), its efficacy in the human body (in vivo) is severely limited by poor bioavailability.

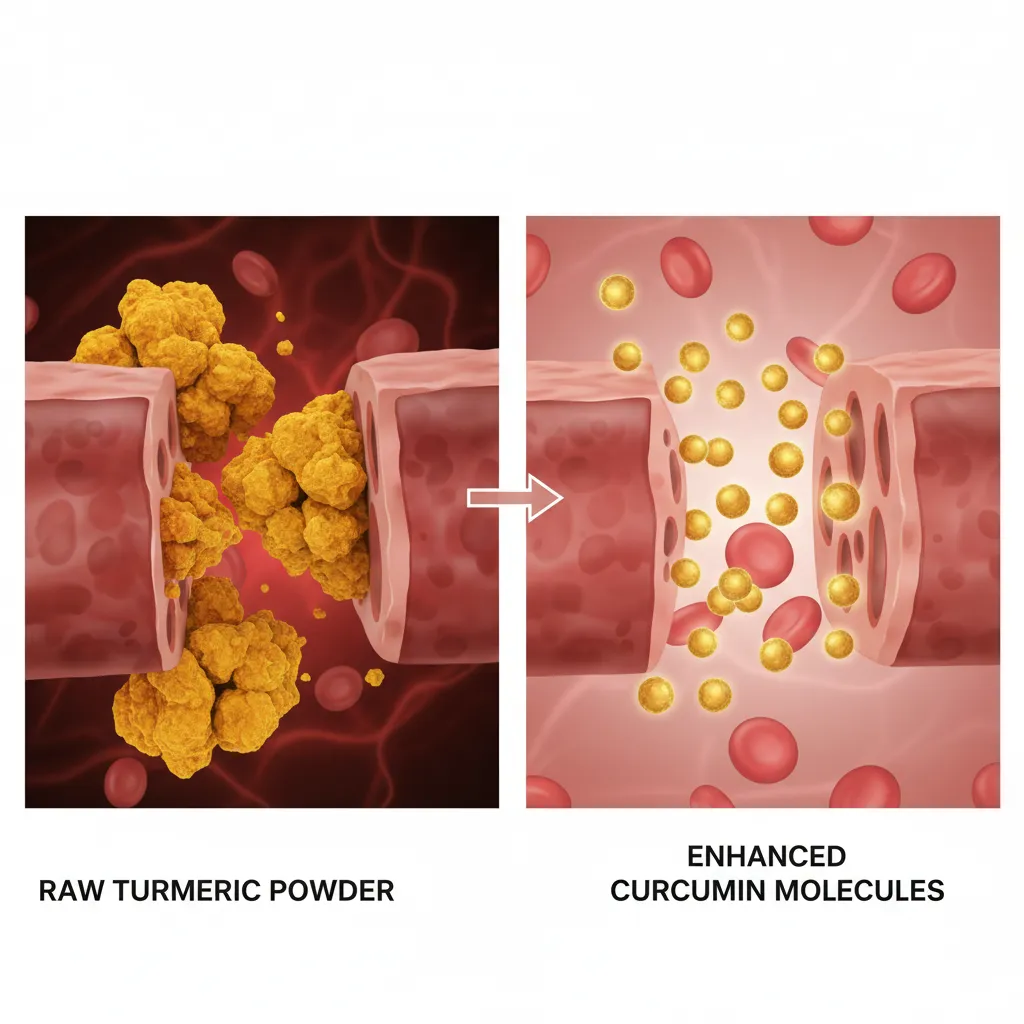

For integrative health practitioners and patients alike, understanding the challenge of curcumin bioavailability is the first step toward unlocking the true medicinal value of turmeric. Consuming raw turmeric root or standard powdered spice often results in negligible levels of curcumin reaching the bloodstream. The vast majority is excreted before it can interact with cellular targets to modulate inflammation or oxidative stress.

This discrepancy between potential and reality has driven decades of research into pharmaceutical and nutraceutical delivery systems. The goal is simple yet complex: to bypass the body’s natural filtration systems that identify curcumin as a foreign substance to be eliminated, thereby allowing it to circulate and exert its healing effects, a principle that also applies to the topical application of Natural Skin Care for Eczema.

Understanding the Biological Barrier: Why is Bioavailability Low?

To appreciate the solutions, one must first understand the physiological barriers. The poor bioavailability of curcumin is attributed to its chemical structure and the body’s metabolic efficiency. Curcumin is a polyphenol that is highly lipophilic (fat-loving) but poorly hydrophilic (water-loving). Since the human body is largely comprised of water, unmodified curcumin tends to clump together in the gastrointestinal tract rather than dissolving into the aqueous environment necessary for absorption.

However, solubility is only the first hurdle. The primary challenge lies in pharmacokinetics—specifically, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). Even if a small amount of curcumin passes through the intestinal wall, it faces the phenomenon known as “first-pass metabolism.”

Rapid Metabolism and Elimination

Upon entering the portal vein from the intestines, curcumin travels directly to the liver. Here, it undergoes rapid conjugation—specifically glucuronidation and sulfation. The liver attaches a glucuronic acid or sulfate molecule to the curcumin, rendering it water-soluble so that it can be immediately excreted by the kidneys. This process is so efficient that studies have shown trace or undetectable levels of free curcumin in the blood plasma of humans who consumed significantly high doses of standard curcumin.

According to research cataloged by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the biological half-life of oral curcumin is extremely short. Without a delivery system to protect the molecule or inhibit these metabolic enzymes, the therapeutic window is virtually non-existent.

The Synergistic Role of Piperine (Black Pepper Extract)

One of the earliest and most commercially successful methods to enhance curcumin bioavailability was inspired by traditional culinary pairings. In Indian cuisine, turmeric is almost always used in conjunction with black pepper. Modern science has validated this wisdom through the isolation of piperine, the alkaloid responsible for the pungency of black pepper.

Piperine functions as a bio-enhancer through a dual mechanism:

- Inhibition of Glucuronidation: Piperine inhibits the liver and intestinal enzymes (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase) responsible for metabolizing curcumin. By slowing down this breakdown, piperine allows curcumin to survive the first pass through the liver.

- Increased Intestinal Permeability: Piperine temporarily alters the dynamics of the intestinal lining, making it easier for compounds to pass through the epithelial barrier and into the bloodstream.

The landmark study famously cited in the industry demonstrated that combining 20mg of piperine with 2g of curcumin increased bioavailability by 2000% compared to curcumin alone. While this is a significant improvement, it is not without limitations. Some individuals experience gastrointestinal irritation from piperine, and because it inhibits liver enzymes, it can potentially interfere with the metabolism of other pharmaceuticals.

Next-Generation Delivery: Liposomes and Phytosomes

As the nutraceutical market has matured, the focus has shifted from merely inhibiting metabolism (piperine) to improving the physical solubility and cellular uptake of curcumin through advanced encapsulation technologies. This has led to the rise of liposomal and phytosome delivery systems.

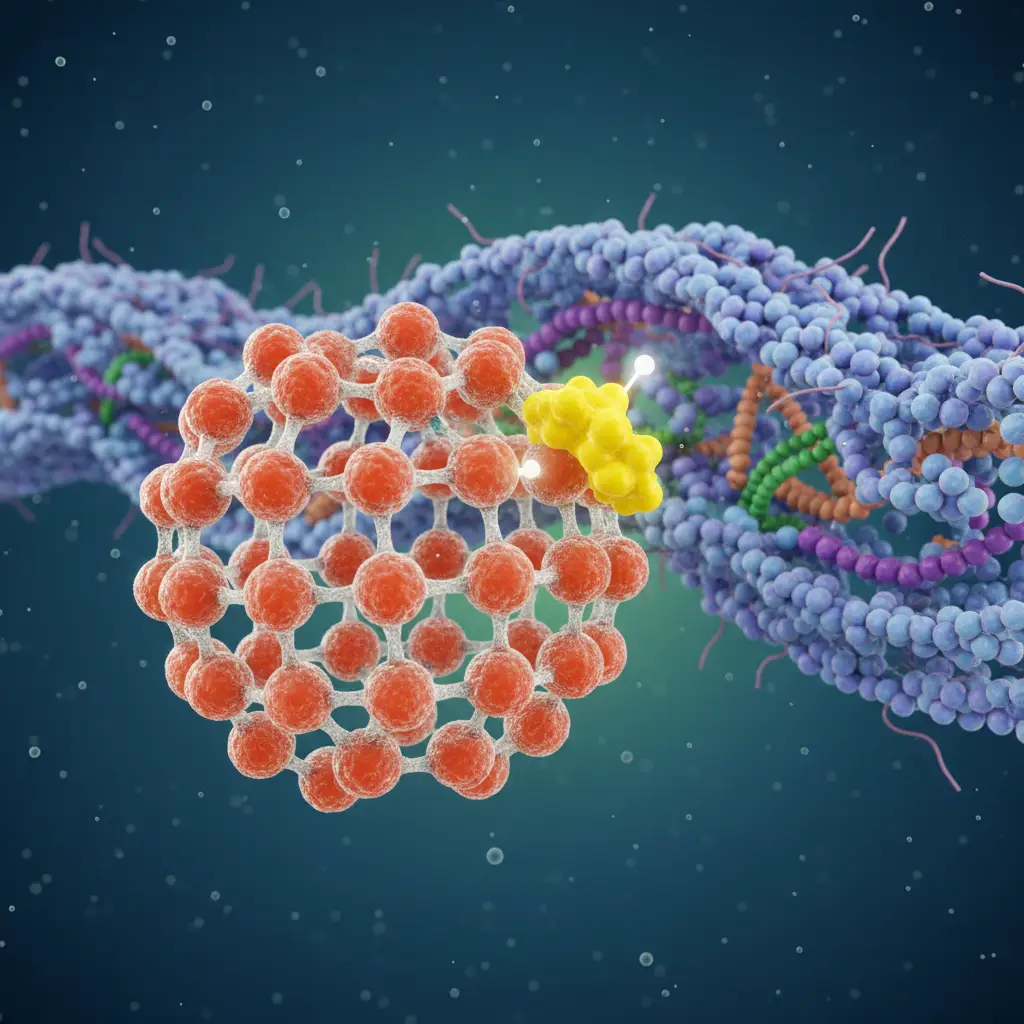

Liposomal Curcumin

Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of one or more phospholipid bilayers. These are essentially microscopic bubbles made of the same material as human cell membranes. When curcumin is encapsulated within a liposome, it is shielded from the harsh environment of the stomach and the metabolic enzymes of the liver.

Because the liposome mimics the cell membrane, it can fuse with cells in the digestive tract, delivering the curcumin payload directly into the lymphatic system or bloodstream. This bypasses the liver’s first-pass metabolism to a significant degree and allows for higher plasma concentrations.

Phytosome Technology

While often confused with liposomes, phytosomes represent a distinct chemical advancement. In a phytosome complex, the curcumin molecule is chemically anchored to a phospholipid (usually phosphatidylcholine derived from soy or sunflower) at the molecular level. This is not just encapsulation; it is a molecular bond.

Phytosomes act as a “chaperone,” guiding the curcumin molecule through the intestinal membrane. This technology improves the miscibility of curcumin in the gastrointestinal fluids and ensures a standardized rate of absorption. Clinical trials suggest that phytosome formulations can achieve absorption rates up to 29 times higher than standard curcuminoids.

Comparing Efficacy: Raw Root vs. Enhanced Formulations

For the consumer, the choice between raw turmeric root, standard powder, and enhanced formulations depends entirely on the health goal. If the objective is general wellness and culinary enjoyment, raw turmeric provides fiber and a broad spectrum of turmeric oils (turmerones) that have their own benefits.

However, for therapeutic interventions—such as managing chronic pain, arthritis, or systemic inflammation—raw turmeric is mathematically insufficient. Turmeric root contains only about 2% to 5% curcumin by weight. Therefore, to obtain a therapeutic dose of curcumin (typically 500mg to 1,000mg), one would need to consume an unpalatable amount of turmeric powder daily.

Enhanced formulations bridge this gap. A high-quality bioavailable curcumin supplement allows the patient to achieve therapeutic blood plasma levels with a manageable daily intake. For example, 500mg of a phytosome preparation may deliver the equivalent bioactive load of nearly 10-15 grams of standard curcumin, ensuring that the anti-inflammatory pathways (such as NF-kB inhibition) are actually triggered.

Clinical Implications for Inflammation and Systemic Health

The quest for bioavailability is not academic; it is clinical. Curcumin is a pleiotropic molecule, meaning it interacts with multiple molecular targets and pathways. Its efficacy in managing conditions like osteoarthritis, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegenerative diseases hinges entirely on its presence in the blood and tissues.

High-bioavailability formulations have shown superior results in clinical trials regarding:

- Joint Health: Reduced pain scores and increased mobility in osteoarthritis patients compared to placebo and standard medication.

- Cognitive Function: Because lipid-based formulations (like liposomes) can cross the blood-brain barrier more effectively, they hold promise for neuroprotection and reducing brain inflammation.

- Cardiovascular Health: improved endothelial function and reduction in oxidized LDL cholesterol markers.

For further reading on the safety and efficacy of turmeric products, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) provides comprehensive resources for patients and practitioners.

Ultimately, when selecting a turmeric supplement, the “total milligrams” listed on the bottle is less important than the delivery system employed. A lower dose of a highly bioavailable form is often more clinically effective than a massive dose of raw powder that the body simply excretes.

People Also Ask

Why is curcumin poorly absorbed by the body?

Curcumin is poorly absorbed because it is hydrophobic (does not dissolve well in water), has poor stability in the pH of the gut, and is rapidly metabolized by the liver and excreted before it can enter the bloodstream.

Does cooking turmeric increase its bioavailability?

Yes, cooking turmeric in oil (fat) and adding black pepper can increase bioavailability. Heat helps increase solubility, and fat provides a vehicle for absorption, while pepper inhibits metabolic breakdown.

Is liposomal curcumin better than curcumin with black pepper?

Generally, liposomal curcumin is considered superior for systemic absorption because it protects the curcumin from digestion and facilitates direct cellular uptake, whereas black pepper only inhibits liver metabolism.

How much turmeric should I take for inflammation?

For therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects, typical dosages range from 500mg to 1,000mg of highly bioavailable curcumin daily. Consult a healthcare provider for specific dosing.

What foods help absorb turmeric?

Foods rich in healthy fats—such as olive oil, coconut oil, avocado, and fatty fish—help absorb turmeric. Additionally, foods containing piperine (black pepper) significantly boost absorption.

Can you take too much curcumin?

While generally safe, extremely high doses of curcumin can cause gastrointestinal upset, nausea, or diarrhea. High bioavailability forms allow for lower effective doses, reducing these side effects.