Yin and yang in body physiology refers to the dynamic equilibrium of opposing biological forces required to maintain homeostasis. In modern medical terms, this duality is mirrored by the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic “fight or flight” versus parasympathetic “rest and digest”) and metabolic processes (catabolic energy release versus anabolic tissue repair), where health relies on the seamless oscillation between these complementary states, a foundation of our work at Home.

The Biological Parallels of Yin and Yang

For thousands of years, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has viewed health through the lens of Yin and Yang—opposing yet complementary forces that govern the universe and the human vessel. While this concept may seem abstract or purely philosophical to the western mind, modern physiology offers striking parallels that validate this ancient wisdom. In the context of yin and yang in body functions, we are essentially discussing homeostasis: the self-regulating process by which biological systems maintain stability while adjusting to changing external conditions.

In the human body, nothing exists in isolation. Every action has a counter-action. Excitement is balanced by inhibition; consumption is balanced by excretion; activity is balanced by rest. When we strip away the poetic language of TCM, we find hard science describing the same phenomena. Yang represents function, heat, excitation, and energy expenditure. Yin represents substance, cooling, inhibition, and tissue repair. Understanding these biological parallels allows us to bridge the gap between integrative health and conventional medicine, exploring The Future of Integrative NZ Herbal Medicine, providing a comprehensive roadmap for optimal well-being.

The Nervous System: Sympathetic vs. Parasympathetic

The most direct physiological correlate to Yin and Yang is the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The ANS operates subconsciously to regulate bodily functions such as heart rate, digestion, respiratory rate, and pupillary response. It is divided into two primary branches that function in a push-pull relationship, identical to the principles of Yin and Yang.

The Sympathetic Nervous System (Yang)

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is the embodiment of Yang. It is responsible for the “fight or flight” response. When the body perceives a threat or requires a burst of activity, the SNS floods the system with catecholamines like adrenaline and cortisol. This is pure Yang energy: it is expansive, active, and heat-generating.

Physiologically, a Yang (Sympathetic) state involves:

- Pupil Dilation: To let in more light and improve vision.

- Bronchial Dilation: To increase oxygen intake.

- Tachycardia: Increased heart rate to pump blood to muscles.

- Inhibition of Digestion: Energy is diverted away from “housekeeping” tasks.

- Glucose Release: The liver releases stored energy for immediate use.

While necessary for survival, a chronic state of Yang dominance—often caused by modern chronic stress—leads to burnout, inflammation, and cardiovascular strain.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (Yin)

Conversely, the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) represents Yin. It governs the “rest and digest” or “feed and breed” activities. This system is active when the body is at peace, allowing for conservation of energy, repair of tissues, and digestion of nutrients. It is cooling, nourishing, and centering.

Physiologically, a Yin (Parasympathetic) state involves:

- Constriction of Pupils: Protecting the eyes and signaling rest.

- Stimulation of Saliva and Peristalsis: Enhancing digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Bradycardia: Slowing the heart rate to conserve energy.

- Glycogenesis: The storage of glucose as glycogen in the liver.

Health is not the dominance of one over the other, but the ability to switch fluidly between them. This flexibility is known as Heart Rate Variability (HRV), a key marker of resilience and longevity.

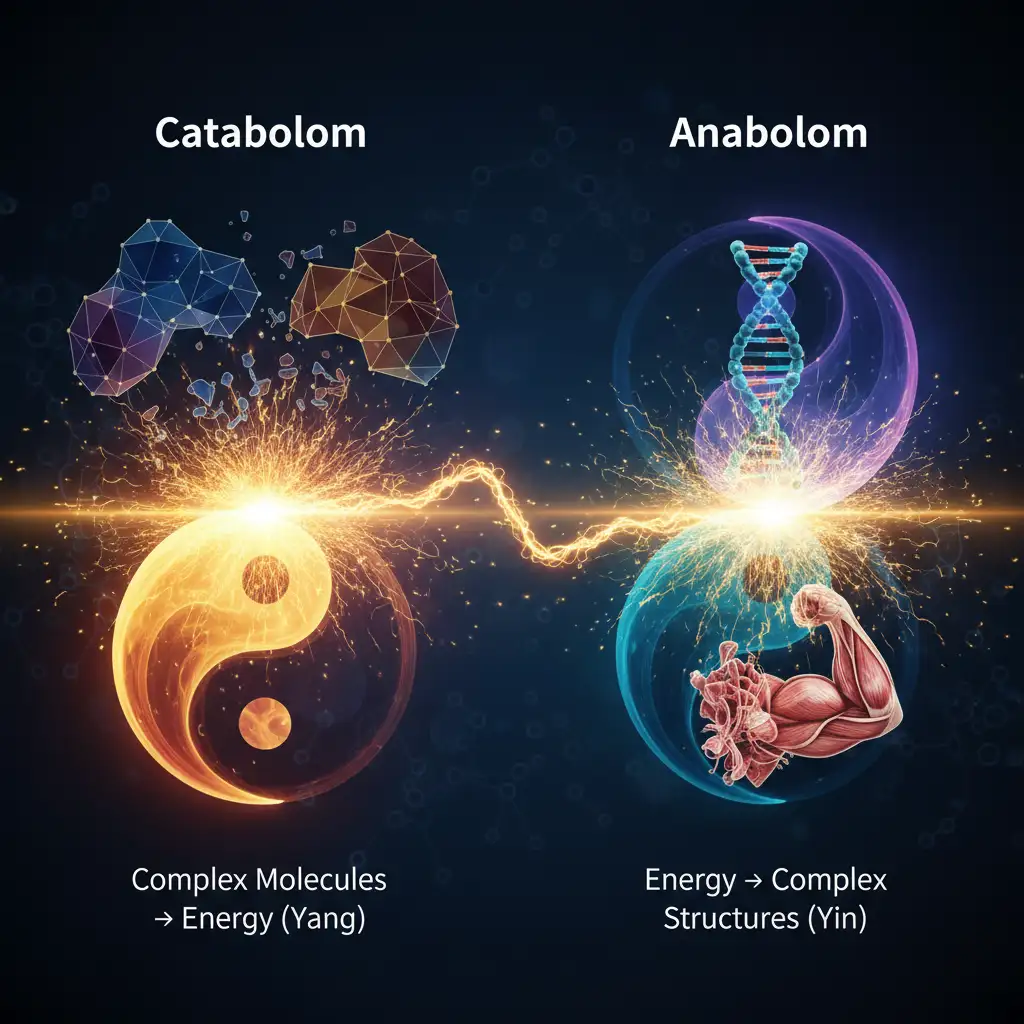

Metabolism: Anabolic vs. Catabolic States

Beyond the nervous system, yin and yang in body chemistry controls how we process energy. Metabolism is the sum of all chemical reactions in the body, and it is split into two opposing phases: Anabolism and Catabolism.

Catabolism: The Yang of Breaking Down

Catabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. This is a Yang process because it releases heat and energy (ATP). When you exercise, you are in a catabolic state; you are breaking down glycogen and fat stores to fuel movement.

Hormones that drive this Yang process include:

- Cortisol: Mobilizes energy.

- Glucagon: Raises blood sugar.

- Adrenaline: Increases metabolic rate.

Anabolism: The Yin of Building Up

Anabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that construct molecules from smaller units. These reactions require energy. This is the Yin aspect of metabolism—the building of substance, the repair of muscle fibers, the synthesis of proteins, and the storage of energy. Without sufficient Yin (Anabolism), the body wastes away, as detailed in Nutritional Herbalism: Global Perspectives & NZ Applications.

Hormones that drive this Yin process include:

- Insulin: Stores energy and builds tissue.

- Growth Hormone: Repairs cells (predominantly secreted during deep sleep).

- Estrogen and Testosterone: Support tissue maintenance and reproduction.

Modern fitness culture often overemphasizes the Yang (the workout/catabolism) and neglects the Yin (the recovery/anabolism). However, biological growth only occurs during the Yin phase. You do not build muscle while lifting weights; you build muscle while sleeping after the weights.

Identifying Yin Deficiency vs. Yang Deficiency

In Integrative Medicine, symptoms are rarely viewed as isolated incidents but as patterns of imbalance. When the dynamic balance of yin and yang in body systems is disrupted, specific clinical presentations emerge. Understanding these can help you identify whether you are suffering from a deficiency of Yin (substance/cooling) or Yang (function/warming).

Signs of Yang Deficiency (Too Much Yin)

When Yang is deficient, the body lacks the fire required to function. Metabolic processes slow down, and the body becomes cold and damp. This is often seen in conditions like hypothyroidism or chronic fatigue syndrome.

Common Symptoms:

- Temperature: Chronically cold hands and feet; aversion to cold.

- Energy: Lethargy, desire to sleep, difficulty waking up.

- Digestion: Bloating, loose stools, undigested food in stool (weak digestive fire).

- Appearance: Pale complexion, water retention (edema), puffiness.

- Mental State: Depression, lack of motivation, brain fog.

Signs of Yin Deficiency (Too Much Yang)

When Yin is deficient, the body lacks the fluids and substance to cool and nourish itself. Consequently, Yang rises uncontrollably, leading to “false heat” or burnout. This is common in high-stress executives, menopausal women, and those with adrenal exhaustion.

Common Symptoms:

- Temperature: Night sweats, hot flashes, heat in the palms and soles (five-center heat).

- Energy: “Tired but wired,” insomnia, restlessness.

- Digestion: Dry stools, thirst, hunger but inability to eat much.

- Appearance: Dry skin, brittle hair, red cheeks (malar flush).

- Mental State: Anxiety, irritability, racing thoughts.

Restoring Homeostasis: Integrative Lifestyle Strategies

Once you have identified the nature of the imbalance, you can utilize lifestyle interventions to restore the yin and yang in body physiology. The goal is not to eliminate one, but to support the weaker side to re-establish the sine wave of health.

Correcting Yang Deficiency (Stoking the Fire)

If you are cold, tired, and sluggish, you need to stimulate the Sympathetic nervous system gently and boost metabolic heat.

- Diet: Consume cooked, warming foods. Ginger, cinnamon, garlic, lamb, and root vegetables. Avoid raw salads and iced drinks which dampen digestive fire.

- Exercise: Engage in interval training or dynamic movements to raise the heart rate. However, avoid exhaustion.

- Therapies: Moxibustion (heat therapy), saunas, and contrast showers (ending on cold) can stimulate the vascular system.

Correcting Yin Deficiency (Nourishing the Water)

If you are burnt out, anxious, and dry, you need to activate the Parasympathetic nervous system and support anabolic repair.

- Diet: Focus on cooling, hydrating foods. Cucumber, melon, pears, bone broths, and healthy fats (avocado, ghee). Avoid spicy foods, caffeine, and alcohol which deplete Yin.

- Sleep: This is the ultimate Yin activity. Aim for bed before 10 PM. The hours between 10 PM and 2 AM are critical for hormonal regeneration.

- Mindset: Meditation and breathwork (specifically extending the exhalation) stimulate the Vagus nerve, triggering the relaxation response.

For more detailed information on how these integrative practices are viewed by federal health agencies, you can visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH).

By viewing your biology through the lens of Yin and Yang, you move away from merely treating symptoms and toward nurturing the fundamental rhythms of life. Whether it is balancing the autonomic nervous system or regulating metabolic hormones, the path to health is always found in the center.

People Also Ask

What are the symptoms of too much Yang in the body?

Too much Yang, or Yin deficiency, typically manifests as heat and hyperactivity. Symptoms include insomnia, anxiety, night sweats, dry skin, high blood pressure, irritability, migraines, and a sensation of heat in the palms and soles of the feet.

How do I increase Yin in my body?

To increase Yin, you must prioritize rest and hydration. Focus on sleep (especially before midnight), consume cooling and moistening foods like soups, stews, and healthy fats, practice meditation to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, and avoid stimulants like caffeine and excessive spicy food.

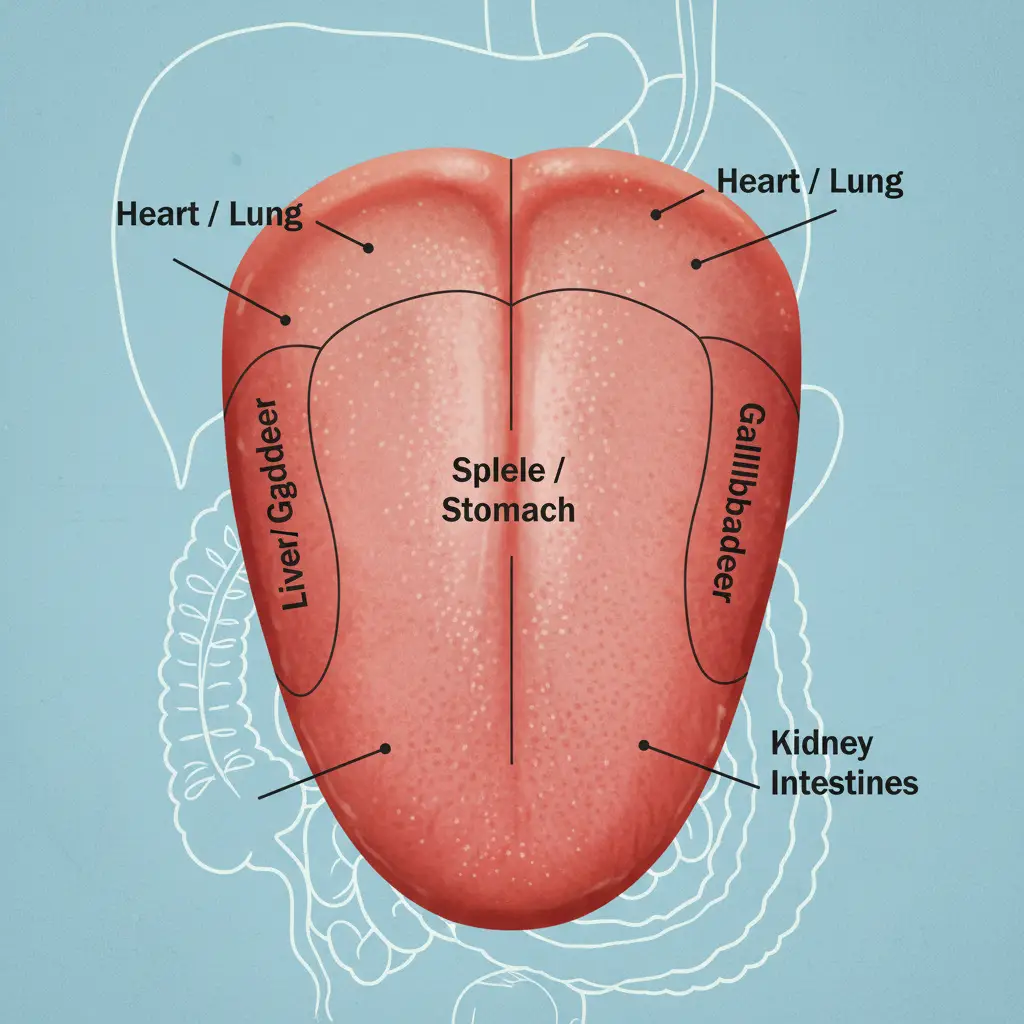

What organs are associated with Yin and Yang?

In TCM, the “Zang” organs (solid) are Yin: Liver, Heart, Spleen, Lungs, and Kidneys. They store essence. The “Fu” organs (hollow) are Yang: Gallbladder, Small Intestine, Stomach, Large Intestine, and Bladder. They transform and transport nutrients and waste.

Is anxiety considered Yin or Yang?

Anxiety is typically considered a manifestation of excess Yang or heat in the Heart and Liver meridians, often stemming from a deficiency of Yin (which anchors the spirit). The racing mind and restlessness are characteristics of unanchored Yang energy.

Which foods are Yin and Yang?

Yin foods are generally cooling and moistening, such as cucumber, watermelon, tofu, and leafy greens. Yang foods are warming and stimulating, such as ginger, garlic, chili peppers, lamb, beef, and alcohol. Cooking methods also affect this; frying adds Yang, while steaming preserves Yin.

How does stress affect Yin and Yang balance?

Chronic stress triggers the sympathetic nervous system (Yang) and depletes the body’s reserves (Yin). Over time, this leads to “Yang rising” symptoms like high blood pressure, followed by eventual burnout or “Yang deficiency” where the body no longer has the energy to function.