How acupuncture works for pain involves a sophisticated neurobiological mechanism where the insertion of fine needles stimulates peripheral sensory nerves, specifically A-delta fibers. This stimulation triggers the release of endogenous opioids like endorphins and adenosine, modulates signal transmission in the spinal cord via the Gate Control Theory, and reorganizes functional connectivity in brain areas associated with pain perception. This approach to natural healing complements Ayurvedic Concepts Applied to Aotearoa Flora and Wellbeing.

The Gate Control Theory of Pain

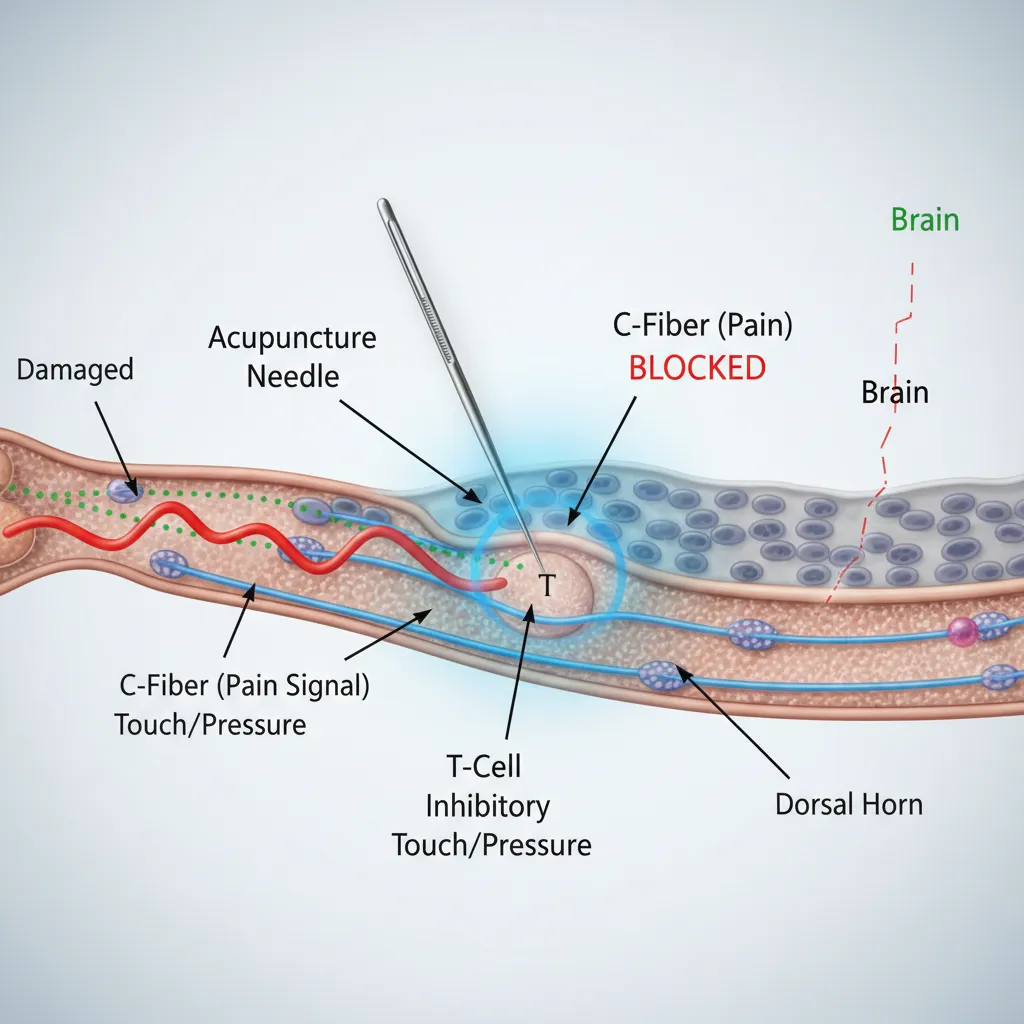

To understand the neurobiology of acupuncture, one must first look at the spinal cord, the highway for pain signals traveling to the brain. The Gate Control Theory, proposed by Melzack and Wall in 1965, remains one of the foundational frameworks for explaining how acupuncture works for pain relief, as featured on our Home page. This theory suggests that the spinal cord contains a neurological “gate” that either blocks pain signals or allows them to continue on to the brain.

Pain signals generally travel along small-diameter nerve fibers known as C-fibers. These fibers transmit the dull, aching sensation characteristic of chronic pain. Acupuncture needles, however, stimulate larger, faster-conducting nerve fibers called A-delta fibers. When an acupuncture needle is inserted and manipulated to achieve the sensation known as Deqi (a feeling of heaviness, numbness, or distention), it activates these faster fibers.

The activation of A-delta fibers inhibits the transmission of pain signals from the slower C-fibers at the level of the dorsal horn in the spinal cord. Essentially, the acupuncture stimulation “closes the gate,” preventing the nociceptive (pain) information from reaching the brain’s processing centers. This creates an immediate analgesic effect that can interrupt the cycle of chronic pain.

Neurochemical Release: Endorphins and Adenosine

Beyond the mechanical blocking of signals in the spine, acupuncture induces a profound biochemical shift within the central and peripheral nervous systems. Research has definitively shown that acupuncture stimulates the release of powerful neurotransmitters and neuropeptides.

Endorphins and Enkephalins

One of the most well-documented mechanisms is the release of endogenous opioids. When the body undergoes acupuncture, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland are signaled to release beta-endorphins and enkephalins into the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid. These are the body’s natural painkillers, structurally similar to morphine but far more potent.

These neurochemicals bind to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, reducing the perception of pain and producing a mild sedative or euphoric effect. This explains why many patients feel a sense of deep relaxation or “acupuncture drunk” immediately following a session.

The Role of Adenosine

More recent research, including pivotal studies published in Nature Neuroscience, has highlighted the role of adenosine, a neuromodulator with anti-nociceptive properties. Tissue injury or inflammation usually inhibits adenosine, but acupuncture has been shown to trigger a localized surge of adenosine at the needle site.

This local release binds to A1 receptors on nerve endings, effectively numbing the area and reducing inflammation. This peripheral mechanism is crucial for understanding how acupuncture works for pain that is localized, such as knee osteoarthritis or localized neuropathies. The interplay between central opioid release and peripheral adenosine accumulation creates a dual-action pain relief system.

Brain Connectivity: What fMRI Studies Reveal

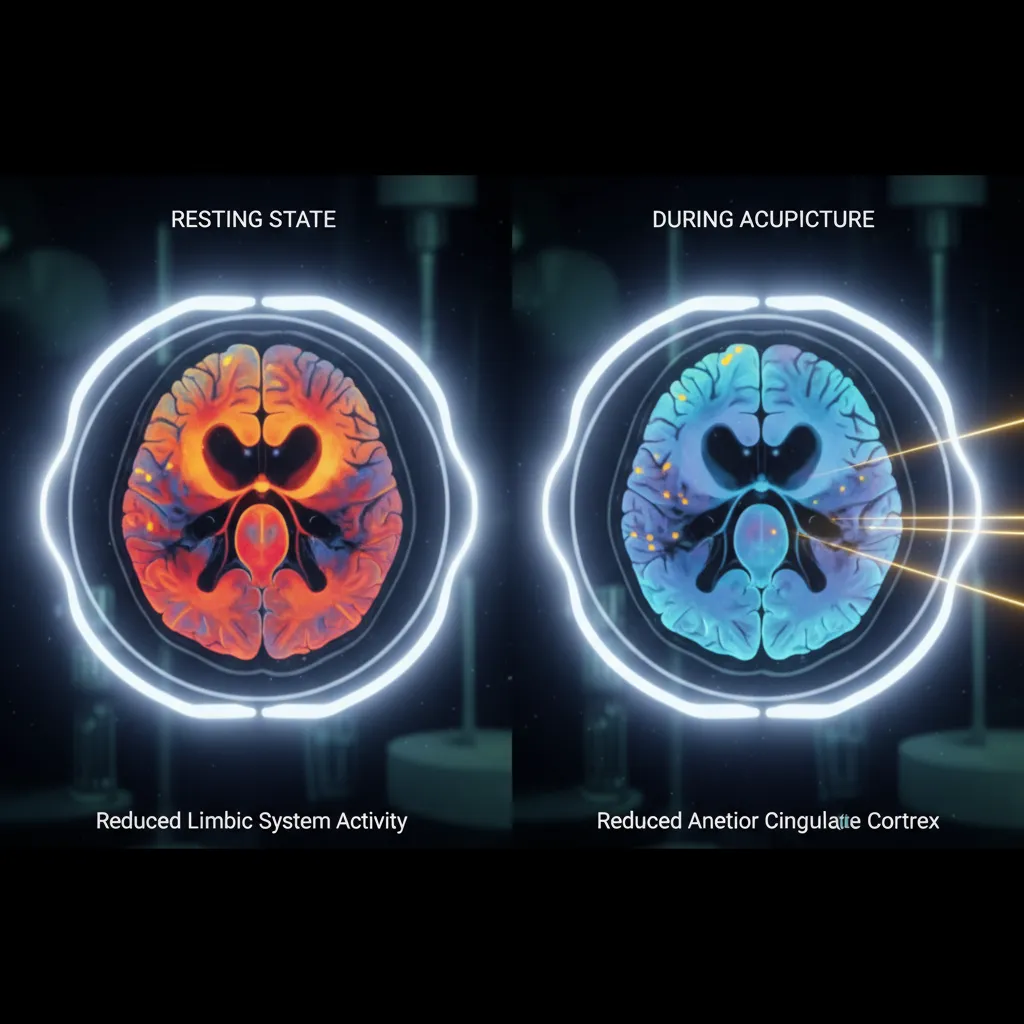

Modern neuroimaging technologies, specifically functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), have allowed scientists to visualize the effects of acupuncture on the living brain. These studies provide compelling evidence that acupuncture does not just mask pain but actively rewires how the brain processes it.

Chronic pain is not merely a sensation; it is a learned neurological pattern. Over time, chronic pain strengthens the connections between the sensory cortex (where pain is felt) and the limbic system (where emotions are processed). This is why chronic pain often leads to anxiety and depression. fMRI studies have demonstrated that acupuncture can deactivate the limbic system, specifically the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex, thereby decoupling the emotional suffering from the physical sensation of pain.

Furthermore, acupuncture has been observed to modulate the Default Mode Network (DMN). The DMN is active when the mind is wandering or ruminating—states often associated with the psychological burden of chronic pain. By down-regulating the DMN and increasing connectivity in the somatosensory cortex, acupuncture helps the brain “unlearn” the chronic pain loop, restoring a more normalized resting state.

Evidence for Back Pain and Migraines

The neurobiological theories are supported by robust clinical data, particularly for conditions that plague millions worldwide: chronic lower back pain and migraines.

Chronic Lower Back Pain

Chronic lower back pain is the leading cause of disability globally. A meta-analysis involving thousands of patients has shown that acupuncture is superior to both no treatment and sham (placebo) acupuncture. The mechanism here is likely a combination of local adenosine release reducing muscle inflammation and the central release of endorphins. By relaxing the paraspinal muscles and resetting the proprioceptive nerve endings, acupuncture breaks the spasm-pain-spasm cycle.

Migraines and Tension Headaches

For migraine sufferers, the prophylactic use of acupuncture has shown remarkable results. Migraines are vascular and neurological events often triggered by stress and cortical spreading depression. Acupuncture helps regulate the autonomic nervous system, shifting the body from a sympathetic “fight or flight” state (which exacerbates vascular tension) to a parasympathetic “rest and digest” state.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), acupuncture reduces the frequency and intensity of tension headaches and prevents migraines as effectively as many prophylactic medications, but with fewer side effects. The regulation of serotonin levels and the modulation of intracranial blood flow are key factors in this efficacy, providing a bridge to Identifying Authentic Rongoā Practitioners and Resources.

The Connective Tissue Hypothesis

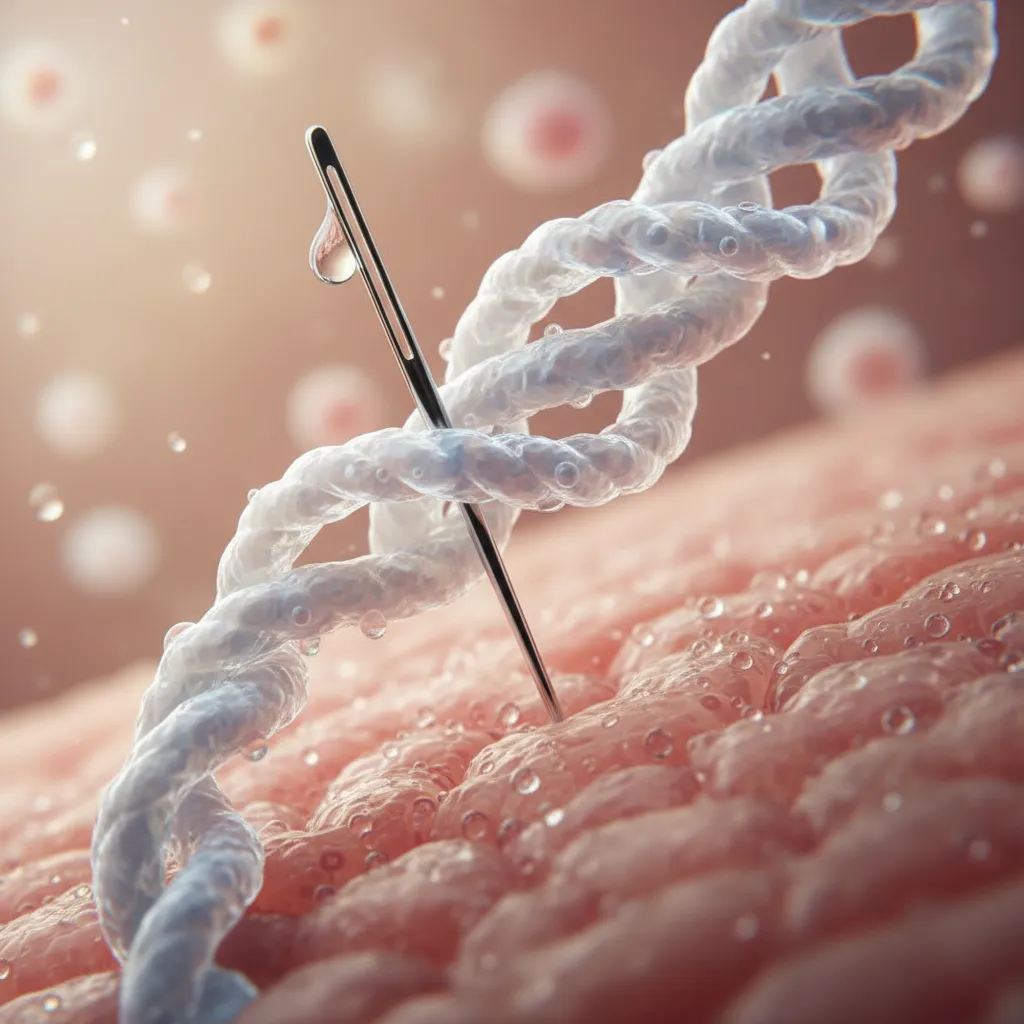

While neurobiology explains much of the analgesic effect, the physical interaction between the needle and the body’s connective tissue cannot be ignored. This is often referred to as mechanotransduction.

When a needle is rotated, collagen fibers wind around the shaft, causing a mechanical coupling between the needle and the tissue. This stretching of the connective tissue fibroblasts causes them to change shape, which triggers a cascade of cellular signaling. This mechanical signal is converted into a bioelectrical signal that travels along the fascial planes.

This hypothesis bridges the gap between the ancient concept of “meridians” and modern anatomy. The fascial planes, which are rich in conductive fluid and nerve endings, may very well be the anatomical equivalent of the energy channels described in traditional texts. Manipulating these tissues reduces fascial restrictions, improves local circulation, and reduces the mechanical pressure on nociceptors.

Safety and Integrative Implementation

Understanding how acupuncture works for pain from a neurobiological perspective validates its place in modern integrative medicine. It is no longer viewed as a mystical placebo but as a precise neurological intervention. However, safety and proper implementation are paramount.

Acupuncture is generally considered safe when performed by a licensed practitioner using sterile, single-use needles. The most common side effects are minor bruising or bleeding at the needle site. Serious adverse events are extremely rare. For patients managing chronic pain with opioids or NSAIDs, acupuncture offers a vital adjunct therapy that may allow for dosage reduction, thereby mitigating the risks of addiction and organ damage associated with long-term pharmaceutical use.

For further reading on the physiological basis of acupuncture, resources like Wikipedia’s medical entry or academic journals offer extensive bibliographies on the subject.

People Also Ask

Does acupuncture actually repair nerves?

While acupuncture does not surgically repair severed nerves, studies suggest it can promote nerve regeneration by stimulating the release of nerve growth factors (NGFs) and improving local blood flow, which provides the necessary oxygen and nutrients for repair in conditions like peripheral neuropathy.

How long does it take for acupuncture to work for chronic pain?

Response times vary. Some patients feel relief after a single session due to immediate endorphin release. However, for chronic conditions, a cumulative effect is necessary. Typically, a course of 6 to 12 treatments over several weeks is required to retrain the nervous system and achieve lasting results.

Is acupuncture a placebo?

No. While the placebo effect can play a role in any medical treatment, numerous animal studies (where placebo is not a factor) and fMRI imaging studies on humans confirm that acupuncture induces specific physiological and neurochemical changes that sham acupuncture does not.

What are the side effects of acupuncture?

Acupuncture is very safe. Common side effects are mild and include slight bleeding or bruising at the insertion site, temporary soreness, or lightheadedness. Serious complications like infection or organ puncture are incredibly rare when treated by a licensed professional.

Can acupuncture replace painkillers?

For many patients, acupuncture can significantly reduce the need for painkillers, including opioids and NSAIDs. While it may not entirely replace medication for severe acute trauma, it is an effective standalone treatment for many chronic pain conditions and a powerful adjunct for pain management.

How deep do the acupuncture needles go?

The depth depends on the location of the point and the patient’s constitution. In fleshy areas like the buttocks or legs, needles may go 1 to 2 inches deep. In thin areas like the hands or head, they may only be inserted a few millimeters. The goal is to reach the appropriate tissue layer to stimulate the nervous system without causing pain.