The history of Rongoā traces the evolution of traditional Māori healing from its origins as a pre-European holistic system grounded in spiritual (wairua) and physical (tinana) well-being. It spans centuries of practice, surviving the legislative oppression of the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907, and has emerged through a powerful revitalization movement to become a recognized, vital component of New Zealand’s modern integrated healthcare landscape. Visit our Home page for more information.

Pre-European Contact: The Foundations of Rongoā

Long before European vessels arrived on the shores of Aotearoa, Māori society possessed a sophisticated, highly structured system of public health and medicine known as Rongoā. This system was not merely a collection of herbal remedies; it was a holistic worldview that integrated the physical, spiritual, family, and mental dimensions of health. In the pre-contact era, illness was rarely viewed as a purely biological event. Instead, it was often seen as a symptom of a disruption in the balance between the individual, the collective, and the natural or spiritual worlds.

The Role of the Tohunga

Central to the history of Rongoā was the Tohunga. These were the experts, priests, and healers chosen from a young age and trained rigorously in the Whare Wānanga (houses of learning). The Tohunga held deep knowledge of tikanga (customs), whakapapa (genealogy), and the medicinal properties of the native flora. They acted as the conduit between the physical realm and the spiritual realm (Te Ao Wairua).

Diagnosing an ailment in this era involved identifying violations of tapu (sacredness). If a person breached spiritual laws or disrespected the environment, the resulting imbalance could manifest as sickness. Treatment, therefore, required restoring this balance through karakia (prayer), water immersion rites, and the application of physical medicines.

Rākau Rongoā: The Pharmacy of the Forest

The physical application of medicine utilized the rich biodiversity of New Zealand’s native bush. Through centuries of observation and trial, Māori identified specific plants for treating injuries, skin conditions, and internal ailments, a tradition that continues with modern practices like Creating Herbal Teas for Common Ailments: A NZ Blend.

- Kawakawa: Used for toothache, inflammation, and digestive issues.

- Harakeke (Flax): Used as a splint for broken bones and for its antiseptic gel.

- Mānuka: Utilized for its strong antibacterial properties, often used in vapor baths or infusions.

The Arrival of Pākehā and the Impact of Colonization

The arrival of Europeans (Pākehā) in the late 18th and early 19th centuries marked a catastrophic turning point in the history of Rongoā. Along with trade and new technologies, settlers brought infectious diseases against which Māori had no natural immunity. Influenza, measles, typhoid, and tuberculosis ravaged the population, causing a demographic collapse that traditional Rongoā practices struggled to contain.

This period created a crisis of confidence. While traditional herbal medicine remained effective for wounds and common indigenous ailments, it was less effective against these virulent foreign pathogens. Missionaries and early colonial doctors seized upon this, promoting Western medicine not just as a biological cure, but as a tool of religious and cultural conversion. They often framed traditional healing practices as “witchcraft” or superstition, actively discouraging the spiritual aspects of Rongoā that were intrinsic to its efficacy.

The Tohunga Suppression Act 1907

The most damaging event in the legislative history of Rongoā was the passing of the Tohunga Suppression Act in 1907. Ostensibly, the Act was designed to protect the Māori population from “quack” doctors and charlatans who were taking advantage of the sick during epidemics. However, in practice, it served to outlaw the cultural and spiritual leadership of the Tohunga.

The Act made it illegal for Tohunga to predict future events or cast spells, effectively criminalizing the spiritual diagnosis and karakia that formed the foundation of Māori healing. While it did not explicitly ban the use of herbal medicine (rākau rongoā), it severed the link between the medicine and the spiritual authority required to administer it correctly according to tikanga. Today, such practices are subject to modern standards like the Medsafe Guidelines for Herbal Product Claims and Advertising.

For more detailed historical context on this legislation, you can review the Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand entry on Rongoā.

The psychological impact was profound. Rongoā was labeled as primitive and dangerous by the state. As a result, the practice did not disappear; it went underground. Families continued to treat their own using knowledge passed down quietly within the home, stripping away the public ceremonial aspects to avoid prosecution.

Survival in the Shadows: The Underground Era

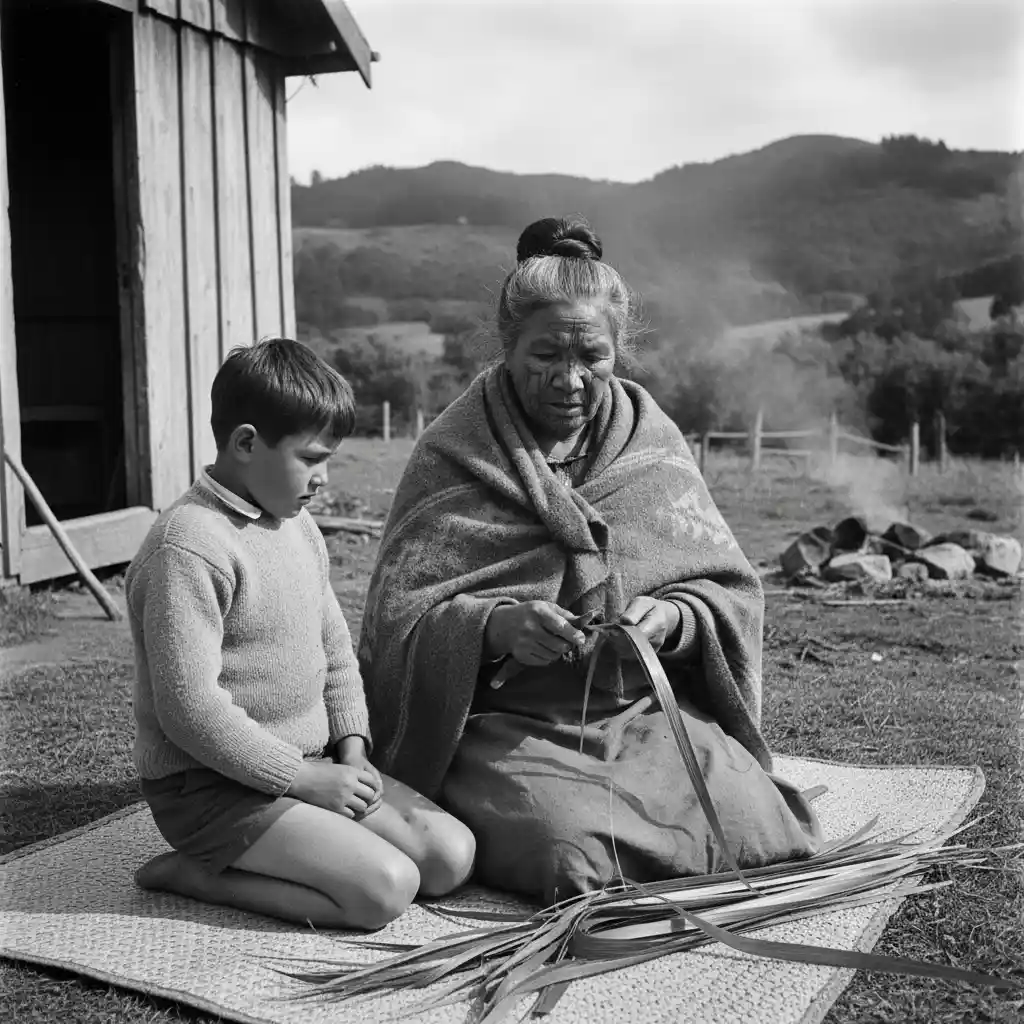

From the early 1900s through to the 1970s, Rongoā existed in a state of quiet preservation. This era is characterized by the resilience of Kuia (female elders) and Kaumātua (male elders) who refused to let the knowledge die. Without the formal institutions of the Whare Wānanga, knowledge transmission became informal, occurring in kitchens and backyards.

During this time, the definition of Rongoā began to shift slightly. While the deep spiritual practices of the Tohunga were suppressed, the practical knowledge of plant medicine remained strong in rural communities. However, the urbanization of Māori following World War II posed a new threat. As families moved to cities, they became disconnected from their ancestral lands and the specific plant sources they knew, leading to a further decline in daily practice.

The Māori Renaissance and Wai 262

The 1970s and 1980s heralded the “Māori Renaissance,” a period of intense political and cultural awakening. As the Māori language (Te Reo) and arts began to flourish again, so too did the demand for traditional healing. The Tohunga Suppression Act was finally repealed in 1962, though the stigma lingered for decades.

A pivotal moment in the modern history of Rongoā was the filing of the Wai 262 claim with the Waitangi Tribunal in 1991. Often called the “Flora and Fauna Claim,” it asserted Māori rights over indigenous knowledge, plants, and culture. The claimants argued that the Crown had failed to protect the tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty) of Māori over their taonga (treasures), including the knowledge of Rongoā.

Te Whare Tapa Whā

During this period, Sir Mason Durie introduced the Te Whare Tapa Whā model of health. This model formally reintroduced the holistic concepts of Rongoā into the mainstream New Zealand health lexicon. It validated what practitioners had known for centuries: that health relies on the four pillars of:

- Te Taha Tinana: Physical health

- Te Taha Wairua: Spiritual health

- Te Taha Whānau: Family health

- Te Taha Hinengaro: Mental health

Modern Integration and the Future of Rongoā

Today, the history of Rongoā is being written in a new chapter of integration and respect. The Ministry of Health (Manatū Hauora) now acknowledges Rongoā Māori as a legitimate health service. Public funding is increasingly available for Rongoā providers, and some hospitals are beginning to facilitate access to traditional healers alongside clinical doctors.

However, challenges remain regarding intellectual property and environmental sustainability. As the global natural health market grows, there is a risk of commercial exploitation of native plants without benefit to Māori. The future of Rongoā depends on protecting the sanctity of the knowledge while ensuring the environment that provides the medicine is preserved.

For further reading on the government’s stance and integration, visit the Ministry of Health’s guide to Rongoā Māori.

People Also Ask

What is the Tohunga Suppression Act?

The Tohunga Suppression Act was a piece of legislation passed in New Zealand in 1907. It was intended to stop “quack” doctors but effectively banned traditional Māori healers (Tohunga) from practicing their spiritual and medicinal crafts, forcing Rongoā practices underground for decades.

When was the Tohunga Suppression Act repealed?

The Tohunga Suppression Act was repealed in 1962 by the Māori Welfare Act. However, the cultural damage and stigma associated with traditional healing persisted for many years after the law was removed.

What are the main components of Rongoā Māori?

Rongoā Māori is holistic and includes rākau rongoā (herbal medicine), mirimiri (massage/bodywork), karakia (prayer/incantation), and water therapy. It focuses on balancing the spiritual, physical, mental, and family aspects of a person.

Is Rongoā Māori recognized by the NZ government?

Yes, Rongoā Māori is recognized by the New Zealand Ministry of Health as a legitimate health service. It is increasingly being integrated into the wider healthcare system, and some services are funded by Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC).

What is the Wai 262 claim?

Wai 262 is a claim lodged with the Waitangi Tribunal in 1991 concerning Māori rights to indigenous flora, fauna, and cultural knowledge. It is crucial to the history of Rongoā as it addresses the ownership and protection of traditional healing knowledge and native plants.

How was Rongoā knowledge passed down?

Traditionally, Rongoā knowledge was passed down orally and through practical demonstration within whānau (families) or formally in Whare Wānanga (houses of learning). After colonization, it was largely preserved through secret oral transmission from elders to selected younger family members.